Last week, D.C. Councilmember and Chair Pro Tempore Kenyan McDuffie took to the pages of The Washington Post to advocate for taxpayer funding for local political campaigns. Under this system, candidates for Council (and a handful of additional races) who agree to only accept small-dollar contributions and completely forgo donations from PACs would receive $5 of government (read: taxpayer) funding for every $1 they receive in voluntary support from D.C. residents.

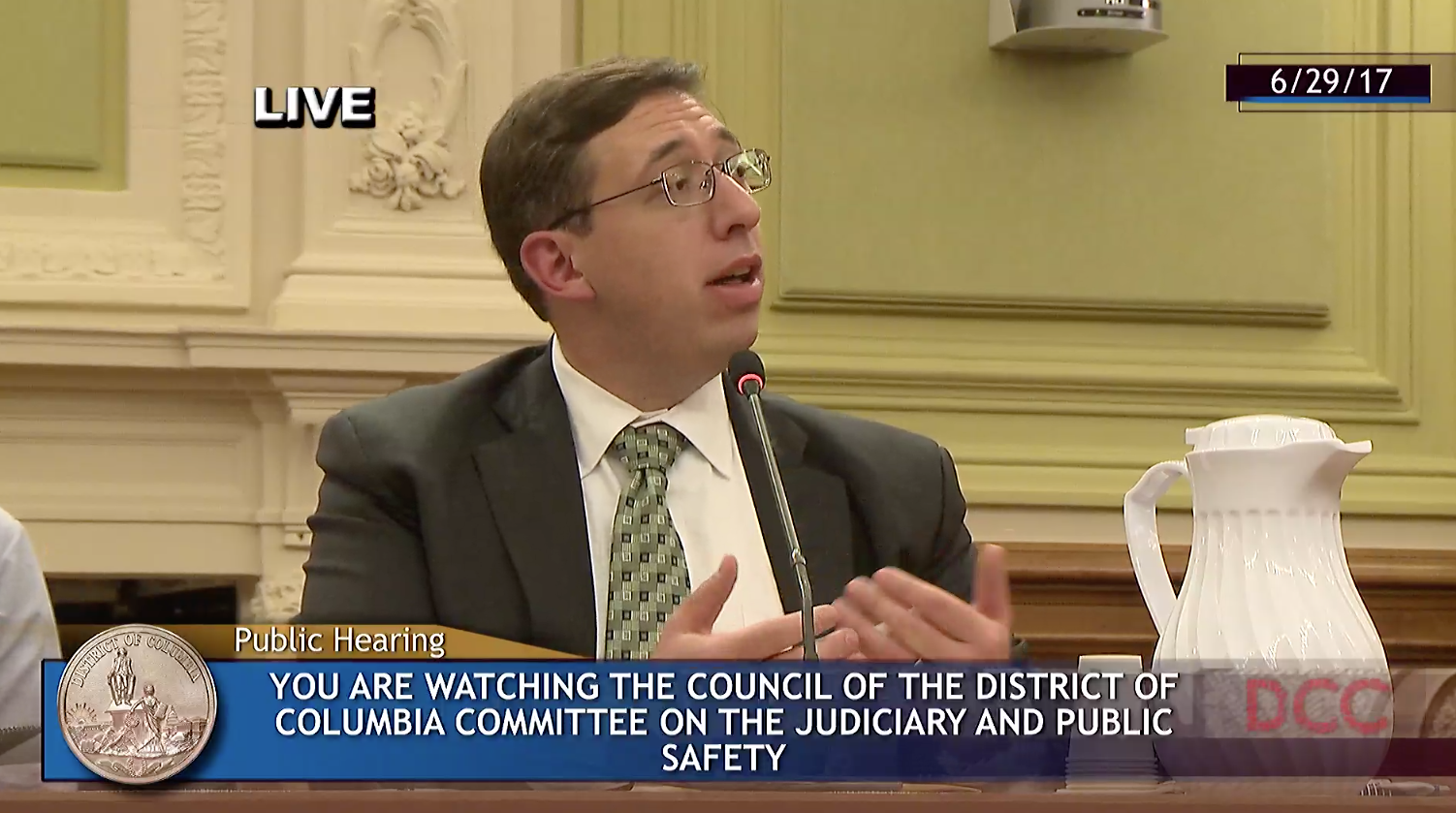

McDuffie calls this proposal an investment in democracy and, indeed, supporters of tax-financing often claim that such a system would achieve many lofty, transformative goals. CCP Attorney Tyler Martinez testified before the D.C. Council in June casting doubt on this optimism – including for reasons outlined below.

In particular, McDuffie cites a few reasons to make his case why Washington, D.C. ought to dole out its residents’ tax dollars to politicians.

First, he points to nearby Howard County and Montgomery County in Maryland, both of which are experimenting with similar public funding schemes. However, as McDuffie points out, the former will not implement its program until the 2022 election cycle, and the latter will only begin in earnest during next year’s elections. What is the point of touting tax-financing systems in other areas before they’ve even begun? It would make far more sense to wait and see the outcomes in these counties before deciding to take D.C. down this path.

Luckily, we can still judge how other big cities around the country have fared with tax-financing programs – and the results aren’t good. Corruption scandals in cities like New York have been made all the worse because they involve taxpayer money rather than just voluntary donations. From 2001 to 2013, New York City granted over $19.2 million in taxpayer-funded subsidies to participating candidates who were later investigated for campaign finance abuses. This is particularly concerning given Washington’s history of corruption in city government. New York City must also provide funds to openly bigoted candidates – just as D.C. would have to do – since such systems cannot discriminate against candidates that wish to participate on the basis of their views.

As noted in Martinez’s testimony to the Council, another major city, Los Angeles, offers numerous examples of politicians gaming the system by reporting fake donations in order to qualify for public funds. (L.A. only provides $2 in matching funds for every $1 in voluntary contributions – imagine the waste if it had D.C.’s proposed 5 to 1 match.) In Seattle’s new program, hundreds of thousands of dollars in taxpayer dollars are going to candidates and incumbents who are already well-known and well-funded. These experiences from other cities should make D.C. residents and their elected representatives on the Council take pause.

McDuffie then argues that the District’s current campaign finance system is flawed because of the demographics of the donor base. Citing a study, he says that white people in 2014 account for just 37% of D.C.’s population, but represent 62% of mayoral donors and 67% of Council donors, which leaves other demographic groups underrepresented. These figures come from a Demos study with questionable demographic numbers. For instance, the study claims that 57% of D.C.’s adult population was black in 2014, but the Census Bureau says that it was actually under 50%. (The Census Bureau says the 2016 population was 44.6% white and 47.7% black.) Whatever the case may be, McDuffie argues that providing matching funds to donors will encourage disadvantaged groups to contribute more than they currently do.

The problem with this argument is that, taken to its logical conclusion, it requires government to manipulate campaign finance laws and regulations to ensure a specific demographic breakdown of political contributors. In any voluntary system – even one that uses taxpayer dollars as an incentive – it is unlikely that the population of people choosing to donate will perfectly match the overall population. Trying to equalize outcomes is destined either to fall short or lead to increasingly invasive government interventions in the electoral process.

Finally, McDuffie concludes that a tax-financing system would also “democratize elections by breaking down the barriers to running for office, amplifying the voices of voters and providing residents an opportunity to participate in the electoral process on par with corporate interests.” Unfortunately, CCP’s research demonstrates that tax-financing programs fall short on all of these goals and more. Indeed, tax-financing programs elsewhere do not reduce lobbyist influence, increase occupational or gender diversity among lawmakers, increase voter turnout, or increase electoral competitiveness.

Analyzing any policy proposal requires weighing costs and benefits. The benefits of tax-financing, at least as described by proponents like McDuffie, do not materialize in practice. Meanwhile, the costs – wasting public money in corruption scandals and forcing taxpayers to subsidize politicians they find objectionable or even offensive – are considerable. Governments should not try to claim a bigger role in the political process at the expense of voluntary actors. As a D.C. resident (who has chosen not to give his money to any local candidate), I encourage Councilmember McDuffie to re-think his stance on gifting our tax dollars to politicians.