Each election cycle debunks another myth about money in politics: when opponents of free speech stoke fears about billionaires buying elections and “corporate takeovers” of democracy, voters expose the sham by proving that our votes must be earned.

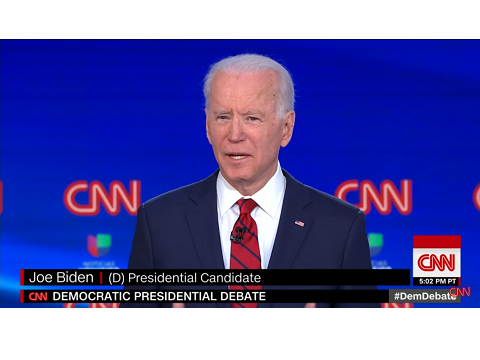

But some politicians continue relying on these tired tropes to push policies that are harmful to free speech. For example, at the most recent Democratic debate, former Vice President Joe Biden played into the disproven narrative that taxpayer-financed campaigns improve democracy. Biden’s platform calls for complete federal funding of all campaigns and a total ban on Americans’ ability to independently support their preferred candidates. In order to make this a reality, he would have to pursue a constitutional amendment.

At first glance, such a policy might seem like a good idea, particularly when it is peddled as a magical cure-all for our nation’s ills. But contrary to advocates’ claims, tax-financed campaigns fail to decrease the incidence of public corruption, fail to reduce lobbyist influence, fail to improve electoral competitiveness, and fail to increase voter turnout or trust in government.

As Mark Twain said, never let the truth get in the way of a good story. Hawking these schemes as an antidote to inequality tugs on the heartstrings of many Americans, who rightly want the average person to have as much opportunity to participate in campaigns as anyone else. But forcing candidates to rely on taxpayer dollars – and forcing taxpayers to fund the campaigns of candidates they may vehemently oppose – is counterproductive to this noble goal.

One reason these policies fail is because they are based on flawed thinking about small-dollar donors. While a small-dollar donor is just as valuable and important as any other kind of donor, anti-speech crusaders often romanticize them as the holy grail of campaign fundraising. Part of this myth rests on the fallacy that small-dollar donors mirror voter preferences. But studies show that small-dollar donors usually come from ideological extremes, while more than one-third of Americans self-identify as moderate.

Seeking to energize low-dollar contributions, candidates gravitate towards emotional appeals about polarizing issues to gin up their base and attract media coverage. It’s difficult for a political outsider to generate media attention – worth its weight in gold – by being the most moderate, least controversial candidate in the race.

At the same time, this system advantages candidates with name recognition who don’t need much help getting their campaigns off the ground. Boosting these sorts of candidates, such as celebrities and incumbents, may actually make it harder for ordinary citizens to run competitive campaigns.

Even if small-dollar donors’ voting preferences were reflective of a broader swath of the public, it would not justify citizens being forced to pay – and candidates being forced to rely on – taxpayer-financed schemes. The entire point of campaigning is to generate public support, not merely to reflect preexisting popularity.

Despite the proven failures of these programs across the country, from Maine to Arizona to New York City to Seattle, proponents will no doubt continue trying to sell their snake oil to unwitting politicians and the public. Buyers should beware.