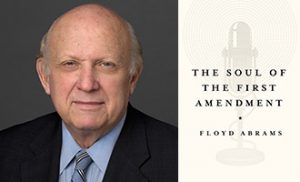

On Monday, the Cato Institute hosted a forum to discuss Floyd Abrams’s new book, The Soul of the First Amendment. Abrams is well known as a scholar and litigator of free speech issues. He is Senior Counsel at Cahill Gordon & Reindel LLP and has been involved in numerous Supreme Court cases, including the famous New York Times Co. v. United States (1971) “Pentagon Papers” case and, more recently, Citizens United vs. FEC (2010). Joining Abrams on the panel were Ronald Collins, a professor at the University of Washington School of Law and author of “First Amendment News” at the Concurring Opinions blog and Ilya Shapiro, Editor-in-Chief of the Cato Supreme Court Review. Roger Pilon, the Director of Cato’s Center for Constitutional Studies, moderated the panel.

The event focused primarily on the content of Abrams’s book, which examines how the First Amendment has provided vastly more protections for freedom of speech and the press in the United States than elsewhere – to a sometimes-controversial extent. One consistent theme during the discussion was that, even among democratic countries, opinions about what even qualifies as free speech differ greatly.

Abrams pointed to Canada, where derisive rhetoric against homosexuals has been actively prosecuted through hate speech laws. He noted that President Trump’s campaign rhetoric against Muslims and Mexicans could be a prosecutable offense in Europe. European courts have even recently found a “right to be forgotten,” which allows individuals to compel companies like Google to remove factual Internet references to them if they are no longer “relevant” to the public. In the U.S., these examples would undoubtedly find protection under the First Amendment.

After Abrams spoke, Collins offered his own analysis of The Soul of the First Amendment – noting how the title evokes free speech as an aspirational and even “spiritual” ethos that not only exists in law, but transcends it. He brought his own example of transnational attitudes about free speech from the World Press Freedom Index by Reporters Without Borders. That Index lists the U.S. at 43rd in media freedom. Does this mean that the American reality of a free press falls short of its ideals, or that it simply has “exceptional” views on the matter?

Take Finland as a counterexample. The country held the top spot in that Index from 2010 to 2016, until its government actually sued a writer in order to censor her book about having an affair with the prime minister. Finland’s ranking understandably dropped in the wake of that controversy, which happened last December. It now ranks third – still remarkably high, given that such a heavy-handed government action against a private author would scarcely be tolerated in the U.S. Abrams argued that, although Finland is indeed strong on press freedoms in general, the suppression of salacious details in the media is actually somewhat consistent with European ideals about personal privacy, which can often outweigh free speech. Hence, the “right to be forgotten.”

Collins summed up the problem with simply chalking up varying standards of free speech protections to cultural differences between countries: a country that does not consider blasphemy, “hate speech,” campaign finance regulations, or commercial speech to be within the realm of free speech protections has an “entirely different” conception of free speech.

Finally, Shapiro focused his time on attacks on free speech by progressives. He mentioned Howard Dean’s recent claims that “hate speech” is not protected by the Constitution, Tim Wu’s writings in The New Republic about the “opportunism” of corporations “hijacking” the First Amendment, and David Savage calling free speech a “weapon” of conservatives in the Los Angeles Times. Shapiro distinguished liberals of the 1960s from those of today’s left who consider free speech to be a manifestation of “privilege” and undue corporate power.

That shift is probably not lost on Abrams, a liberal who now finds himself in agreement with conservatives on most campaign finance and free speech issues. Shapiro hypothesized that this partisan gap is due to the fact that most progressives currently see government as a force for good rather than a potential threat to free expression, and wish to use its power to equalize outcomes on behalf of the marginalized. Meanwhile, conservatives – who see themselves as marginalized in academia and the media – find much to distrust in government regulation of speech, Shapiro explained.

Shapiro pointed to the backlash against Citizens United as a key example of hostility to the First Amendment. As he explained, Citizens United was a straightforward case of government trying to dictate who could speak, how much they could speak, and when they could speak. Despite the rhetoric of opponents, that decision has not stifled opposing viewpoints, prevented less well-funded politicians from winning elections, or kept activists from identifying (and vilifying) certain politically-active individuals. Still, those opposed to the decision have insisted on legal and legislative measures to restore regulatory power to the government, even if it means amending the First Amendment to the Constitution. Shapiro blamed misinformation from political leaders (including, unfortunately, former President Barack Obama) for the fact that many Americans have a knee-jerk opposition to and poor understanding of Citizens United.

The fact that the forum was able to touch on so many topics – from campaign finance to campus protests to libel law – is a testament to how free speech (and threats to its existence) continues to be such a salient issue today. This is just as it was during the days of the Pentagon Papers, the Espionage Act of 1917, and even from the beginning of this country’s independence, when the Founders debated whether to have a Bill of Rights at all. The “firstness” of the First Amendment that Abrams emphasized is something that Americans would do well to remember, as it is a critical part of the very soul of this country.