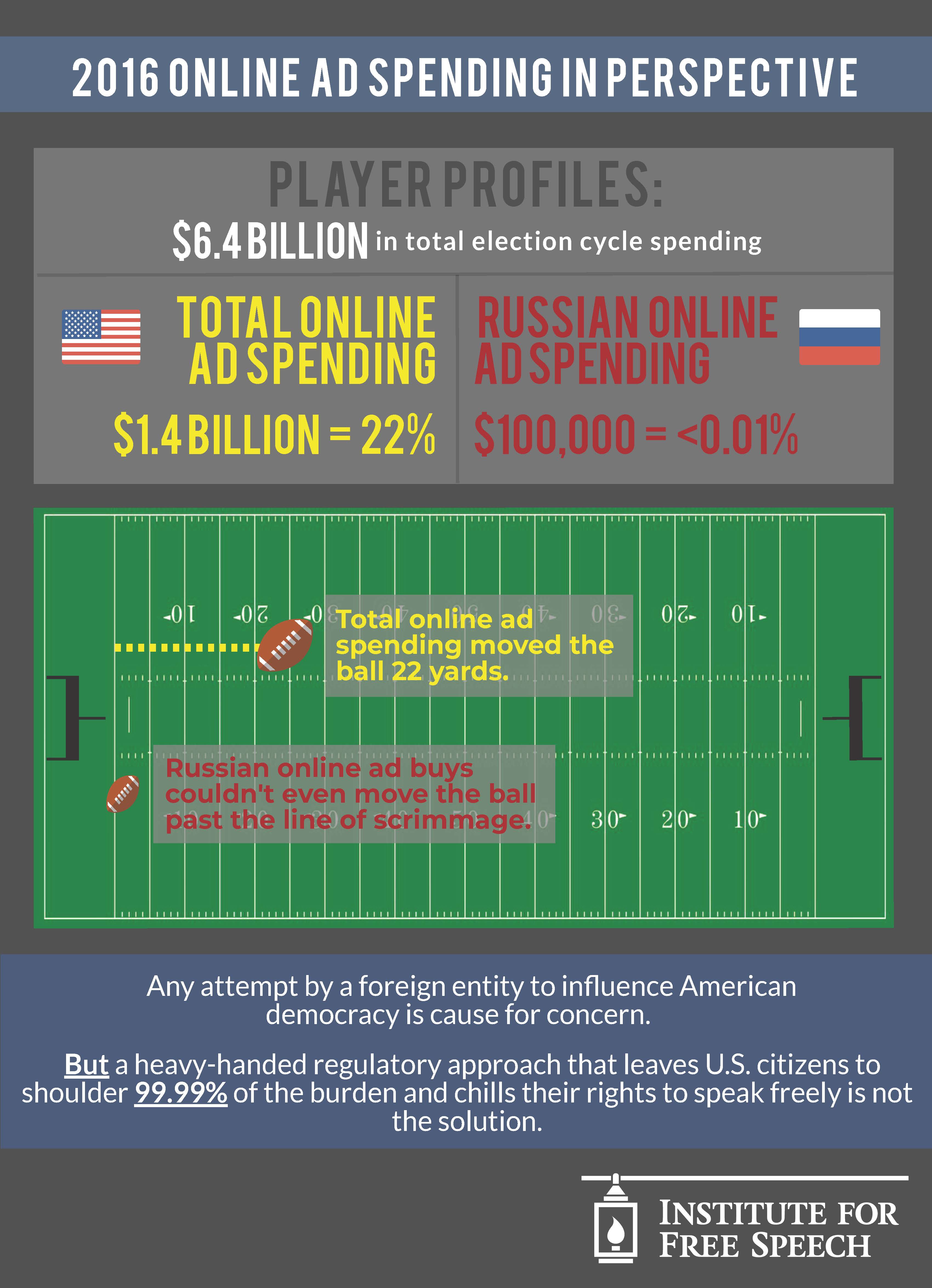

With over 70% of Americans regularly saying they disapprove of Congress’s job performance, it’s no wonder that politicians are searching for scapegoats. Both parties appear to have found some in the form of major Internet companies like Google, Facebook, and Twitter. Unfortunately, free speech is getting caught in the crossfire.

Last week, hearings in both the House and Senate saw politicians of both parties beat up Big Tech leaders for their supposed sins. According to members of Congress, the social media giants ban too much speech, too little speech, and the wrong kinds of speech.

Republicans portrayed the companies as opponents of conservative speech and allies to liberal causes. Democrats portrayed them as self-interested businesses asleep at the wheel as dangerous groups exploit their platforms to stoke bigotry and misinformation. Both agreed that social media companies are too big, too powerful, and harm American politics.

Few suggested that free and unfettered speech, while messy and chaotic, serves the Internet and American democracy better than government regulation. The old consensus that the Internet improves politics by allowing more people to speak at lower cost finds fewer and fewer advocates. Now even the legal protections undergirding the modern Internet are coming into question.

In a Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on the Constitution hearing, Chairman Ted Cruz accused social media companies of harboring bias against conservatives. No one bats an eye when this sort of opinion is expressed about MSNBC or The New York Times. When aimed at Facebook or Twitter, however, it is apparently justification for government action. Senator Cruz suggested that possible avenues of recourse might be to reform Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, open an antitrust investigation, or pursue charges of fraud against the companies.

Underlining Senator Cruz’s anger at the platforms was his framing of Section 230 as a “bargain” tech companies made with the American people: Internet service providers get immunity from lawsuits over user-generated content (“an effective subsidy,” as Cruz called it), and the American people get neutral public forums for the free exchange of ideas. By allegedly discriminating against users based on their politics – a claim vigorously disputed by the witnesses from Facebook and Twitter as well as Ranking Member Mazie Hirono – the platforms had broken that deal, calling the premises of Section 230 into question.

Senator Cruz’s framing is an echo of an argument that others, usually on the left, make about tax-exempt nonprofits. The story goes that government, and by extension the public, has given these groups a benefit (immunity from lawsuits in the case of Internet service providers, and tax-exemption in the case of nonprofits), and they are exploiting it to further their own political goals.

In both cases, however, no such bargain ever took place. Critics of politically-active nonprofits forget (or willfully misinform) that these groups have always been involved in public affairs and that political committees are also tax-exempt entities. Senator Cruz has forgotten, or misrepresents, that Section 230 was created to encourage platforms to remove objectionable content, not to enforce “neutrality.” Had Internet companies simply been treated as publishers, they would have been liable for any illegal content that appeared on their platforms. The only way Internet companies could have avoided liability would be to adopt a completely hands-off approach to content moderation, but this presented its own problems. Congress did not want the fear of lawsuits to prevent platforms from, for example, removing pornography or adopting policies to protect children. So they created Section 230 to give platforms a free hand to restrict content as they see fit. There is simply no requirement that platforms be neutral to receive Section 230 protection.

While the Constitution does not demand Section 230 immunity for Internet platforms, as Antonin Scalia Law School Professor Eugene Kontorovich reminded the Subcommittee, it has been widely recognized as critical to the Internet’s remarkable success. Repealing Section 230 without a well-considered replacement would throw the baby out with the bathwater. The “social” part of social media could not exist. For politicians to start down this path without ready alternatives is reckless, to say the least.

This is especially true given the lack of trust each party demonstrates towards the other on this issue. If the members of the Subcommittee feared anything more than letting social media companies decide what speech to allow and what speech to ban, it was letting members of the other party set the rules.

The crux of the Republican argument against Big Tech is that they are stealth liberals, putting their thumbs on the scale of Internet expression to favor Democratic viewpoints. And for Democratic Senator Hirono, the social media companies were guilty of just about everything – hate speech, harassment, misinformation – except bias against conservatives. If a conservative’s speech is removed, it probably deserves to be, Senator Hirono suggested.

“Maybe they shouldn’t post lies about Planned Parenthood selling baby body parts? Maybe they shouldn’t inflame religious tensions by misrepresenting the tenants of one of the world’s major religions?” she said, telling conservatives to take a closer look at what they are posting.

Where Senator Hirono did find common ground with Senator Cruz was in concluding that social media platforms are “too big,” and that anyone who uses the Internet knows that “the online world can be a pretty vile place.” She urged the Subcommittee to redirect its focus to “the real issues facing America like hate speech, voter suppression, like the emoluments clause.” (Don’t ask me.)

Overall, Senator Hirono may oppose Republican efforts to regulate the Internet, but she appears happy to do so herself when Democrats are back in charge of the Senate.

That same week, Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi managed to echo both Cruz and Hirono. She also criticized social media platforms and said that Section 230 may be in “jeopardy.”

“230 is a gift to them, and I don’t think they are treating it with the respect that they should,” Pelosi said. “For the privilege of 230, there has to be a bigger sense of responsibility on it, and it is not out of the question that that could be removed.”

At the moment, then, it appears the biggest impediment to government regulation of Internet speech on an unprecedented scale is simply divided government. Is sweeping regulation only a matter of time? Whoever can break the gridlock may destroy both the Internet and free speech in the process.

However little Americans may trust companies like Google, Facebook, and Twitter – and that skepticism is surely warranted – it would be immensely dangerous to empower politicians to decide what speech is acceptable online. Congress has demonstrated time and again that it does not understand the Internet, and its members display motivations for regulating social media that vacillate between ignorance and partisanship. As governments across the world crack down on online speech, and major Internet companies cow to their demands, users who care about free speech must take it upon themselves to advocate for a free and open Internet – or else the only remaining questions are who will actually kill it, when, and how.