On Tuesday, NBC News reported that Google would ban two websites, ZeroHedge and The Federalist, from its advertising services. Such a ban could be an enormous blow to an ad-supported website. By some measures, Google Ads commands over 30% of the entire digital ad business worldwide.

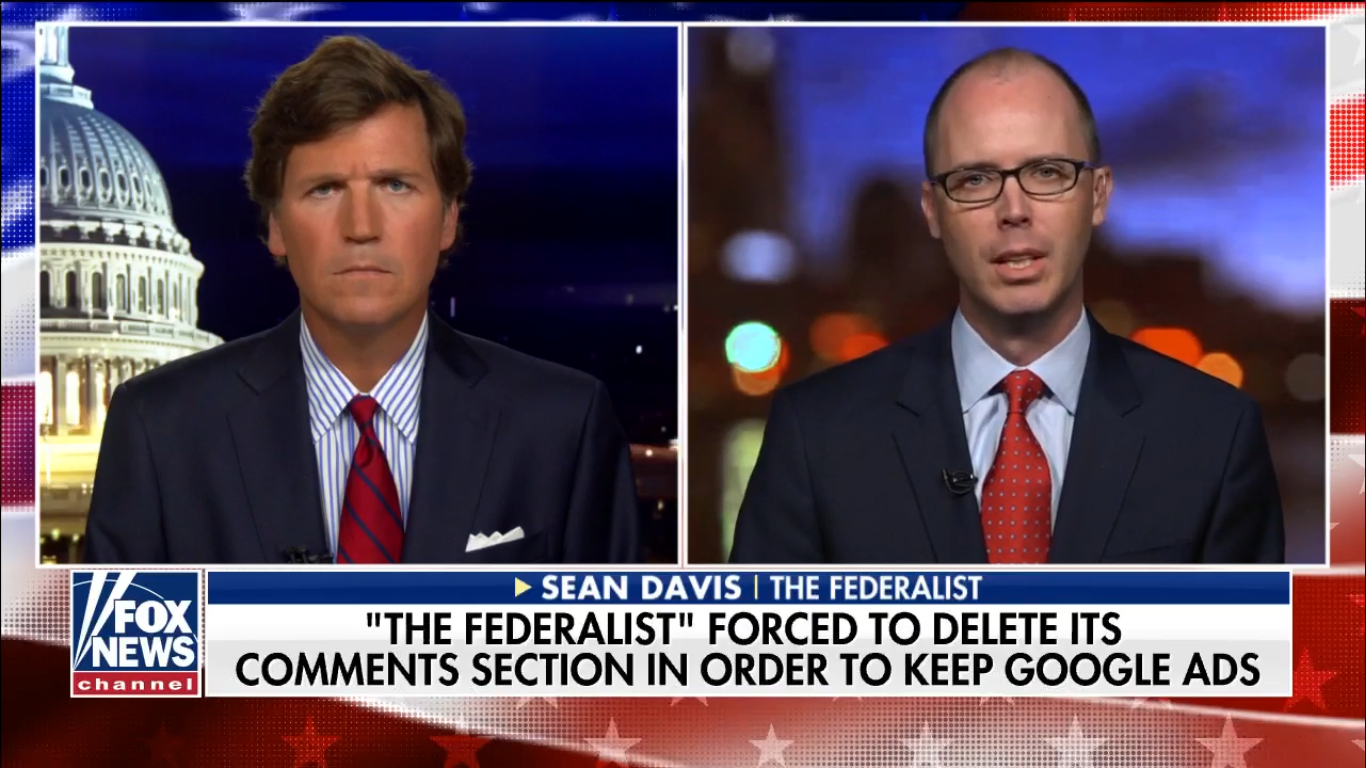

A Google spokesperson added that The Federalist was in violation of its policies, not because of its articles, but because of content in its readers’ comments. The Federalist responded by immediately removing all user comments from its website. Google then said the matter was resolved, and the site would not be demonetized.

For some on the right, the hypocrisy angle of this story is seemingly too good to pass up. Some Republicans (and some Democrats) have called for revoking federal law’s protection of online platforms against liability for user-generated content. Many legal experts argue that these protections, established in 1996 through Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, are essential to internet platforms’ ability to function because they could not possibly vet the billions of pieces of content that users post every day. Yet here is one of those very platforms punishing a conservative news site for user-generated content.

As is often the case, the simple narrative hides some contradictory facts. Mike Masnick of Techdirt noted that articles on his site had also faced temporary demonetization from Google Ads in the past over the same exact issue, throwing a bit of cold water on conservatives’ Big Tech bias theory. But Google’s policies appear to be enforced in a complaint-driven process, which creates problems of its own. NBC News put these two sites under a microscope and brought the results to Google. Will they do the same for left-leaning outlets? Or will a right-leaning site, like say, Fox News, raise similar issues with Google over comments on a progressive blog?

Google should revisit its policies so that they can’t be gamed as easily. But conservatives should be asking: would revoking Section 230 make things any better?

The Federalist’s response suggests that it would not. The instant the site faced financial repercussions for the content of its user comments, it removed all user comments. It did not go through and separate good from bad. It just chucked all the comments out in one fell swoop.

While The Federalist plans to bring back its comments section in due course, it’s easy to see how others could make a different choice. If these incidents were to continue, many websites might decide that user comments aren’t worth the trouble. Especially if some group goes hunting for comments that violate Google’s rules (or even posts problematic comments themselves), hoping to damage a particular publication.

The stakes with Section 230 immunity are even higher than a loss of ad revenue. The risk to a platform is that it will be sued and have to pay out for illegal content that users are able to slip past the refs. The incentives to restrict speech will be stronger.

Conservatives in favor of changing Section 230 argue that web platforms would be less likely to censor voices on the right if their protection from liability could be revoked for bad content moderation practices. But here we see the far more likely outcome of allowing financial penalties for users’ speech: platforms would ban a whole lot more speech.

To avoid ruinous lawsuits without Section 230 protection, web platforms would be forced to make a stark choice: allow all lawful user content on their platforms, including likely pornography, spam, and terrorist propaganda, or prohibit all user content, inevitably putting many mainstays of today’s internet out of business. Congress created Section 230 to avoid this no-win scenario. It wanted to encourage platforms to moderate offensive content while still allowing users a voice online.

Proposals from politicians like Senator Josh Hawley aim to condition this immunity on vaguely defined standards of what good faith moderating entails. This could play out much the same way as simply revoking it. Platforms will live in fear of costly litigation arguing that they failed to abide by these uncertain standards. Just like the era before Section 230, the all-or-nothing approach to content moderation will be the safest way to proceed.

Ultimately, the First Amendment protects the right of internet companies like Google to decide what speech they want to be associated with. But the practical effect of revoking Section 230 would be internet platforms cracking down on more speech than ever before. That won’t help conservatives get a fairer shake online.

User speech often counters the narratives put forth by legacy media outlets. Attacks on Section 230 threaten only one side of that equation. Whether conservatives currently have it good or bad on the web, revoking its legal protections won’t make it better.