Editor’s Note: This is the second in a series of posts examining the speech-limiting effects and record of failure of taxpayer-financed campaign programs, specific to provisions included in the so-called “For the People Act,” which House Democrats have introduced as H.R. 1 in the 116th Congress. Part I is available here, part III is available here, and part IV is available here.

H.R. 1, also known as the “For the People Act of 2019,” is much better understood as the “For the Politicians Act” due to its generous taxpayer handouts to politicians. But it’s worth asking: What kind of politicians might benefit most from the taxpayers’ generous “gifts”?

And the match is very generous – six dollars for every dollar donated, up to a $200 donation. In some cases, the match can reach nine to one.

Certainly, incumbent politicians with large fundraising networks will benefit, as evidenced by the programs in both New York City and Seattle. The more donors a candidate already has, the more matching funds they’ll receive. But who else?

Candidates with close ties to advocacy or labor groups that have large canvassing operations will likely benefit. These groups, even those that sponsor political committees, may not solicit contributions through their affiliated PAC. That’s because the bill requires that a matchable contribution be “made directly by an individual to the candidate…and not [be] forwarded from the individual making the contribution to the candidate … by another person.” [Note: there is an exception for certain PACs like ActBlue or EMILY’s List.] Yet if the bill becomes law, it’s a safe bet that these canvassing operations will be made available for hire to favored candidates. For a measure touted as insulating candidates from special interests, that’s a major loophole.

Another likely winner under tax-financed campaigns will be candidates who take extreme positions that appeal to small, concentrated groups of voters.

Rather than appealing to the middle of the electorate, a viable strategy may be to “play to the base” where supporters are more passionate – and partisan. Given the low turnout in party primaries, taking extreme positions to appeal to a base may even become the dominant strategy.

Traditionally in American politics, political parties have been instrumental in candidate selection and have served as a moderating force overall. Parties have a large incentive to win and therefore want to nominate candidates who appeal to broad swaths of the American public and can win over swing voters. Political parties have used their fundraising apparatuses to favor candidates who fit this mold. Meanwhile, candidates who were viewed as extreme often received little support or funding from the party. While party support didn’t always prevent these candidates from winning elections, the parties’ gatekeeping mechanism certainly provided a moderating function on the types of candidates who were nominated.

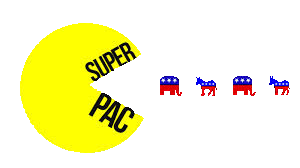

Taxpayer financing of campaigns threatens to provide a final crushing blow to this important party role.

Look no further than the last election, where some of the best small dollar fundraisers were Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders, respectively. Neither candidate had long been a member of the party whose nomination they sought, yet both came close to securing it, and one did. Programs that turbocharge small dollar candidate fundraising and relegate the parties to the sidelines will only lead to more candidates following their example.

Finally, consider how much more difficult it would be for political parties to raise money. What sensible donor would give $50 to a political party if she could give the same $50 to a candidate of that party and have taxpayers foot the bill for $300 or more to match it?

The subsidy will most likely drive donors away from the moderating forces exerted by parties and toward individual candidates. This will likely have the effect of further starving parties that were already hit hard by changes to campaign finance law in 2003.