“Campaign finance laws… easily can serve as incumbent-protection devices, insulating current officeholders from challenge and criticism,” now-Supreme Court Justice Elena Kagan wrote in a 1996 University of Chicago Law Review article. Kagan warned that “there may be good reason to distrust the motives of politicians when they apply themselves to reconstructing the realm of expression.”

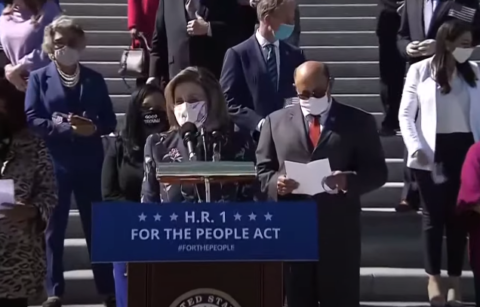

Recent commentary from politicians in Congress validates the wisdom in Kagan’s writing. In comments celebrating the House of Representatives’ partisan passage of H.R. 1, Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) explained that achieving the Democrats’ legislative agenda will be easier if certain voices are “not weighing in.” In other words, suppressing speech is not an unfortunate side effect of the bill’s complex and onerous regulations on advocacy. It’s a primary motivation.

As the Senate begins debate on its own version of the bill, S. 1, Democrats should consider the short-sightedness of their anti-speech motives. Not long ago, several key Republicans, still in control of the Senate, expressed their own interest in suppressing political speech by “regulating money.”

In the heat of the toughest reelection fight of his political career, Senator Lindsey Graham (R-SC) told his “good friend,” Senator Sheldon Whitehouse (D-RI), “me and you are going to come closer and closer about regulating money” in politics.

Why? In Graham’s words, “Because I don’t know what’s going on out there, but I can tell you there’s a lot of money being raised in this campaign.”

At the time, Graham was facing a Democratic challenger with more resources for the first time ever. In fact, his opponent raised more than any Senate challenger in history. Those funds helped make the race surprisingly competitive in pre-election polls in a state where Republican Senate candidates usually cruise to victory. All that competition spurred Graham’s demand to know, “OK, how do we control this?”

While Senator Whitehouse is well-known for obsessively demanding access to right-leaning groups’ donor lists, Graham’s target was ActBlue, a group that provides an online fundraising platform for Democratic candidates and left-leaning advocacy groups.

“Where’s all this money coming from ActBlue coming from?” he asked The Hill. The answer is simple: Americans exercising their First Amendment right to fund political speech. But in the midst of a campaign season in which Democratic challengers were outraising Republican incumbents all over the country, some fellow Senate Republicans joined Graham in calling for an investigation into ActBlue and left-leaning donors. H.R. 1 and S. 1, by radically transforming the Federal Election Commission into a partisan agency, would enable these sorts of politically motivated investigations.

You might think that Senator Whitehouse would shy away from touting Republican incumbents’ nakedly self-interested attack on Americans’ First Amendment right to contribute to the candidates and causes they support. Instead, he claimed credit for convincing Republicans to take aim at left-leaning donors and then suggested they support his legislation that would expose donors on “both sides” to harassment and intimidation. Both of the bills he touted are incorporated into H.R. 1 and S. 1.

One such proposal, the so-called “DISCLOSE Act,” was separately reintroduced in the both the House and Senate just days before the House passed H.R. 1. That bill, and its provisions in H.R. 1, would force groups speaking about legislative issues to publish the names and addresses of their major supporters. Consequently, groups that respect the privacy of their supporters will avoid engaging in communications that trigger the donor exposure requirements, and many Americans will think twice before giving in the first place. As Senator Charles Schumer (D-NY), a primary architect of the DISCLOSE Act, put it when the bill was first introduced in 2010, “The deterrent effect should not be underestimated.” And just in case there was any doubt about the intent, Schumer reiterated that the bill is motivated by a desire to deter civic engagement again in 2014.

Laws that discourage Americans from participating in democracy benefit those in power, on both sides. Senator Whitehouse has apparently decided to lean into this reality in his quest for bipartisan support. For his part, Senator Graham has already supported a bill that would do tremendous harm to Americans’ (and his constituents’) ability to engage in political speech online. He was a cosponsor of the deceptively named “Honest Ads Act,” which is also included in H.R. 1 and S. 1.

Democrats in Congress seem to believe that suppressing political speech is the key to achieving their policy goals. Aside from the fact that kneecapping Americans’ ability to challenge the powerful is never an appropriate aim of legislation, Democrats should remember they won’t control Washington forever. That’s especially true when certain powerful Republicans’ appetite for abusing speech regulations and overbroad disclosure requirements to stifle opposition has been clearly demonstrated.

If new ideas and fresh faces are to have any chance of breaking through, civic engagement must not require Americans to navigate a maze of impossible-to-understand regulations and requirements. By exposing more Americans to politically motivated targeting, imposing more regulatory burdens on advocacy, and enabling partisan enforcement of the rules, H.R. 1 and S. 1 would entrench the status quo and make future policy change far more difficult.

Justice Kagan argued 25 years ago that “First Amendment law, as developed by the Supreme Court over the past several decades, has as its primary, though unstated, object the discovery of improper governmental motives.” If the speech-restricting provisions in H.R. 1 and S. 1 ever make their way to the Court, the “motive-hunting” now-Justice Kagan spoke of should be no difficult task.