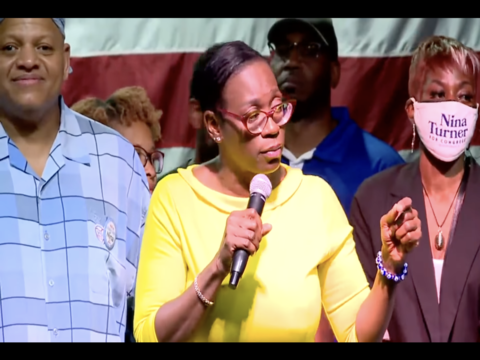

In Tuesday’s Democratic primary in Ohio’s 11th Congressional District, former Ohio State Senator Nina Turner was defeated by Cuyahoga County Councilwoman Shontel Brown. Turner doesn’t seem to be taking the loss so well.

“We didn’t lose this race – the evil money manipulated and maligned this election,” she proclaimed during her “concession” speech.

As it turns out, as of late July, Turner had outraised her opponent by $2.5 million. She also benefited from celebrity and high-profile endorsements, which surely didn’t hurt her ability to stay in the news cycle and raise small dollar donations. If she wasn’t talking about her campaign funding, what exactly is the source of this supposedly evil money?

I surmise it has something to do with comments she made earlier Tuesday. She tweeted about the “billionaire-funded Super PACs” trying to “buy” the election.

Of course. Why not blame everyone’s favorite scapegoat: groups of like-minded citizens pooling their resources to support or oppose political candidates independently of those candidates’ campaigns. How wicked!

Turner blasted independent groups for their “misleading smears,” but admitted she actively refuted the claims she disagreed with and provided a strong counternarrative. Why wasn’t her pure, wholesome money effective in combating the messages she didn’t like? Could it be that her campaign simply did not resonate with voters?

A convincing case can be made that groups of Americans didn’t like Turner’s stance on issues related to Israel. As a result, they decided to throw financial support via a super PAC behind Turner’s opponent, who had a different perspective on the debate. This is democracy in action. Super PACs offered an important tool for Americans with divergent beliefs about foreign policy to express their opinions on the candidates’ views in a prominent race. These Americans aren’t “evil,” simply because their political advocacy opposed Turner’s candidacy. And, of course, Turner’s own campaign benefited from super PAC support as well.

It’s incredibly difficult to run for office, especially in a prominent race under the glare of the national spotlight. Nearly all political candidates deal with what they believe are unfair attacks. Indeed, Turner’s opponent said the ads targeting her were false. Whether those messages are funded by one million small donors, twenty big donors, or one single celebrity – what does it matter, so long as a candidate is able to mount a strong defense? Nina Turner strikes me as someone more than capable of generating positive press coverage and correcting the record, so it’s unclear what role she thinks money played in the contest.

Unless, of course, Turner is yet another politician who perpetuates myths about campaign spending to serve her own interests. Perhaps it’s more convenient to believe that she lost because of her opponents’ alleged lies rather than the inconvenient truth that her own campaign’s message wasn’t popular enough.