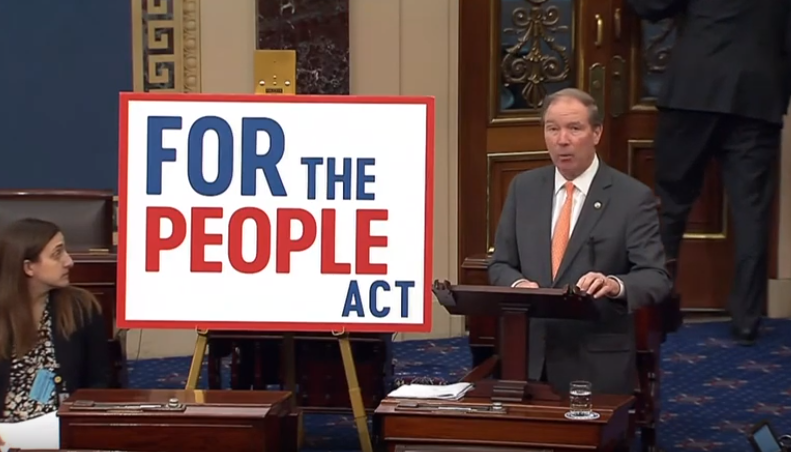

Senators Jeff Merkley (D-OR) and Tom Udall (D-NM) describe H.R. 1, the so-called “For the People Act,” as “legislation to put power back in the hands of the people.” This is a chillingly Orwellian way to describe a bill that would radically expand the federal government’s power over Americans’ political speech.

The singular purpose of numerous provisions within H.R. 1 is to include more types of speech within the government’s regulatory purview. In fact, much of the bill is dedicated to defining new categories of speech that would trigger burdensome and invasive reporting requirements for groups speaking about policy issues – taxes, healthcare, the environment, immigration, you name it. The obvious effect of these provisions would be self-censorship.

When groups must choose between inviting legal scrutiny and not engaging in certain communications, many will choose the latter. Complying with complex regulations on speech requires groups to hire expensive attorneys. And when, as in H.R. 1, the line between an unregulated communication and a regulated communication is vague or indiscernible, even hiring attorneys may not eliminate the risk of facing penalties.

While Merkley and Udall claim to be taking on billionaires, big corporations, and “insidious forces,” low-budget and grassroots groups would bear the brunt of H.R. 1’s speech-chilling provisions. Resource-rich organizations can afford attorneys and the risk of fines. Other groups will simply self-censor communications they fear may cross a regulatory line.

Many of the bill’s regulations on speech are aimed at forcing issue advocacy organizations to expose the names and home addresses of their donors. Because the vast majority of these organizations respect the privacy of their supporters, many would avoid speech that may trigger donor disclosure. In many cases, under H.R. 1, merely mentioning an elected official is all it takes to invite the heavy hand of government.

Making matters worse, a reconfigured, partisan Federal Election Commission (FEC) would be responsible for enforcing H.R. 1’s vague and unclear provisions. Since its creation in 1974, the FEC has been a bipartisan, six-member agency. No more than three commissioners may be affiliated with the same political party. In conjunction with other safeguards, this feature ensures that enforcement actions receive bipartisan approval and prevents partisan weaponization of the law. But H.R. 1 would recklessly transform the FEC into a five-member agency under the control of the president.

Currently, commissioners themselves elect the chair of the FEC to a one-year term, and commissioners can only serve as chair once in a six-year term. Under H.R. 1, a chair with broad, new power to control the enforcement priorities of the agency would be hand-selected by the president. A five-member agency effectively controlled by a campaign speech czar appointed by the president is a recipe for politically motivated, selective enforcement of the law.

How does increasing the president’s power to harass political opponents return power to the American people? Senators Merkley and Udall may want to ask themselves how they’d feel about a political appointee of President Trump having the sole power to compel testimony from and issue subpoenas to Democratic campaigns, groups, operatives, and donors. Or, they could heed late Senator Alan Cranston’s (D-Ca.) prescient warning, delivered during debate on legislation creating the FEC:

“We must not allow the FEC to become a tool for harassment by future imperial Presidents who may seek to repeat the abuses of Watergate. I understand and share the great concern expressed by some of our colleagues that the FEC has such a potential for abuse in our democratic society that the President should not be given power over the Commission.”

Merkley and Udall assert that Americans’ level of spending on speech in the run-up to the 2018 midterms is evidence of a problem “getting worse.” That members of Congress view robust political speech as a problem in need of a legislative solution is, in itself, cause for concern. Touting H.R. 1 as that solution reveals that the senators are not only aware of, but endorse, the bill’s chilling effects on constitutionally-protected speech. H.R. 1 does not lower contribution limits for campaigns, parties, or PACs. It also does not impose contribution limits on independent groups or spending limits on any entity, presumably because both are decidedly unconstitutional – although Democratic senators would like to change that. If Merkley and Udall believe H.R. 1 will reduce spending on political speech, they must be counting on the bill’s regulatory burdens and invasive requirements to chill such speech.

The senators claim that “[m]uch of this election spending is in the form of undisclosed ‘dark’ money, making it impossible for the American people to know who is funding election ads and with what motives.” Unless you’d describe less than 3% as “much of,” this statement is false – and has been for some time. Furthermore, due to long-standing disclaimer requirements, Americans do know what groups are funding these ads. And the money these groups spend on the ads is publicly disclosed. Nonprofits pejoratively described as “dark money” groups aren’t required to publicly identify their donors because – unlike PACs, super PACs, and candidates’ committees – they do not exist primarily to engage in election-related advocacy.

Sens. Merkley and Udall declare that Congress must pass the “For the People Act” in order to “keep” our republic. But our republican government of, by, and for the people rests upon the foundation of the First Amendment, most essentially its protection of Americans’ right to speak about government free from state interference. By aggressively undermining that protection, H.R. 1 would threaten our self-governed republic, not preserve it. The “For the People Act” would hand more power to politicians, not the people.