[Update: The Supreme Court will hear arguments in FEC v. Cruz on Wednesday, January 19. In December, the Institute for Free Speech filed a second amicus brief with the Court, available here.]

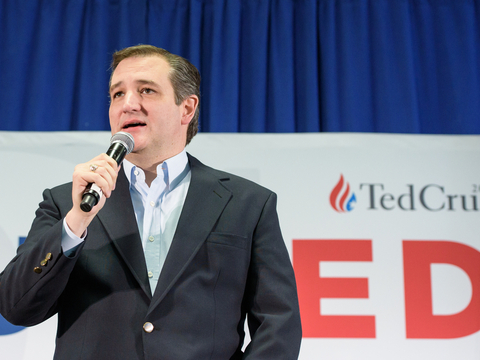

Senator Ted Cruz’s recent victory over the Federal Election Commission in a loan-repayment case clarified important First Amendment principles. Late last week, the Institute for Free Speech asked the Supreme Court to make those principles the law of the land. Our amicus brief urges the Justices to not merely affirm the district court’s ruling in favor of Cruz but, in order to give precedential weight to the affirmance and provide guidance to lower courts, potential litigants, and others interested in campaign finance law, also to adopt its reasoning nationwide in a brief memorandum opinion.

Cruz challenged a provision of the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002, otherwise known as McCain-Feingold, that restricts candidates’ ability to use campaign donations received after the election to pay back personal loans to their campaign. The D.C. District Court’s decision in the case should serve as a model for other courts in two respects. First, the decision focuses on the real-world effect of restrictions on political speech. In ruling for Cruz, the court recognized that “laws that disincentivize candidates from loaning money to their campaigns will result in less political speech,” our amicus brief notes.

In doing so, the district court avoided the legal weeds that courts too often get lost in, namely the distinction between “expenditures” and “contributions” established in Buckley v. Valeo. The Supreme Court divided these categories in 1976 to explain why it struck down limits on how much campaigns may spend while upholding limits on how much donors may give. Ever since, courts have been more willing to strike down restrictions on “expenditures” than “contributions,” reasoning that they are more directly related to speech rights.

This approach can sometimes be more confusing than clarifying, however, and the Cruz campaign’s case offers one recent example of that problem. Here, the law affects contributions by restricting a candidate’s ability to reimburse personal loans to their campaign. Yet it also clearly restricts speech by depriving the campaign of funds it would use to speak, as the district court recognized. In these circumstances, courts must not miss the First Amendment’s forest for Buckley’s trees.

As IFS Senior Attorney Don Daugherty writes in the Institute’s amicus brief, the distinction between contributions and expenditures can be a helpful heuristic, but “it is not an end in itself.” Rather, it is the First Amendment that “provides the lodestar for courts to follow – namely, political speech must be largely unfettered by regulation – and any analysis must begin with that premise before delving into whether the challenged regulation relates to contributions or expenditures.”

Second, the Supreme Court should embrace the district court’s careful application of closely drawn scrutiny. Courts have long differed over just how closely to evaluate the government’s evidence for speech restrictions under this standard. The Institute’s amicus brief notes Libertarian National Committee v. FEC and Lair v. Motl as recent cases where closely drawn scrutiny was misapplied to uphold restrictions on contributions despite a lack of evidence.

In Cruz v. FEC, the district court vetted the FEC’s evidence and found it didn’t hold up to scrutiny. In some ways, the evidence was nonexistent. For instance, the FEC could not name a single instance of quid pro quo corruption arising from unrestricted loan repayments, despite the fact that many states have no such limits. Moreover, the base limits that apply to all contributions to federal candidates exist to satisfy that very purpose. The government failed to prove that its additional restrictions on loan repayments were necessary to prevent corruption.

The Supreme Court now has an opportunity to provide guidance to the lower courts about how to evaluate similar cases, avoid the errors of LNC and Lair, and apply proper scrutiny to the government’s claims before blessing restrictions on campaign contributions. It should seize the moment by issuing summary affirmance in Federal Election Commission v. Ted Cruz for Senate, with a memorandum opinion embracing the fundamental First Amendment principles outlined in the district court’s ruling.

Our First Amendment rights, not the Court’s decision in Buckley, lie at the heart of campaign finance law. Courts must always carefully vet the evidence before allowing government to restrict them.