Is the purpose of increasing voter turnout to make politics more democratic, or to make politics more dominated by Democrats?

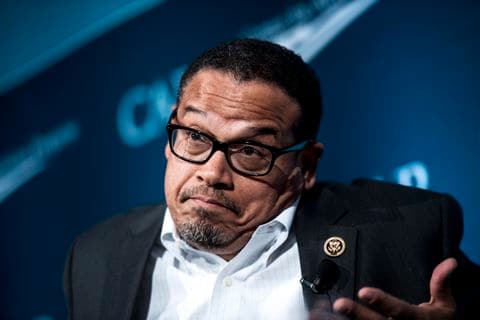

Let’s ask Rep. Keith Ellison, who wrote about his plan to boost turnout in The Nation this week:

“One in three. That’s how many people eligible to vote actually did in 2014. It was the lowest turnout since World War II.

We’ve seen the results of declining turnout. Democrats have lost 910 state legislative seats since 2008 and have only 18 governors. Republicans have the biggest majority in Congress since the Truman administration.

I am launching a Voters First program to put voters at the center of our politics with effective grassroots organizing and a commitment to increasing turnout.”

According to Ellison, a Voters First program would “commit[] first to boost voter turnout by 3 to 7 percent,” use “best practices for effective field organizing,” “partner with candidates up and down the ticket,” and “set a goal to raise 25 percent or more of their contributions from low-dollar donors.”

But the details of Rep. Ellison’s plan are far less interesting than his apparent motivations for launching it. Notice that he did not say voter turnout is low and we should raise it. He said voter turnout is low, which benefits Republicans, and therefore we should raise it.

In other words, this isn’t principled. This is political. You can see it again in the examples he chooses to highlight what could be achieved with higher voter turnout. Each is an issue associated primarily with the Democratic Party:

“Like the marchers from Selma to Montgomery, Americans are organizing for justice through movements to raise the minimum wage, prove that black lives matter, combat climate change, and more.

Our democracy is in trouble when issues supported by the majority of Americans, like increasing the minimum wage or passing immigration reform, can’t even get a vote in Congress.”

But that’s not all. Although Rep. Ellison is not proposing a law, and is merely advocating a style of campaigning he thinks other candidates should adopt, he nonetheless falls prey to a common trope of the would-be censor when he specifically calls out ads that criticize candidates rather than praise them. Here he is not pushing back against money in politics or antipathy but pushing back against the content of speech. He writes, “while TV ads may help convince a voter whom to support, there is little evidence TV ads help turn out new voters. In fact, negative ad wars can turn off voters by reinforcing cynicism about politics.” (emphasis in original)

Rep. Ellison is free to urge candidates to play nice, but he misunderstands the effects of TV and negative ads. Studies find that campaign advertising makes citizens both more knowledgeable and more interested in elections. Further, a comprehensive 2007 study of the effects of negative campaign ads does not support the claim that they somehow damage politics, or even that they work particularly well to begin with. (“What remains is to try to understand why negative campaigning is so pervasive and why the old saws about its effectiveness for its practitioners and its destructiveness to the political system continue to be repeated,” the paper explains in its conclusion.)

Taken together, Rep. Ellison appears to want more Democrats to vote and fewer people to criticize him. That’s perfectly understandable, but it’s also completely self-serving. The impression, on the whole, is that Ellison is less interested in hearing from the voices of voters and reacting accordingly, as he is in finding a subset of non-voters that agree with his preconceived partisan viewpoints. That approach in the end will not be helpful to political participation, and will dissuade Republicans from supporting genuinely good ideas. In short: improving civic engagement should be about the process, not the outcome.

CCP supports political participation in its many forms regardless of who benefits. That’s why our plan for increasing turnout has less to do with telling candidates how to run their campaigns, and more to do with telling government to stay out of the way.