PDF of analysis available here

Analysis of Connecticut H.B. 7329 (2019):

“Dark Money and Disclosure” Bill is Extremely Opaque

and Unconstitutionally Overbroad

By Eric Wang, Senior Fellow[1]

Introduction and Executive Summary

The Institute for Free Speech (“IFS”)[2] provides the following analysis of H.B. 7329 – a bill pending before the General Assembly that supposedly addresses “dark money and disclosure of foreign political spending and of political advertising on social media.”

While H.B. 7329 purports to be a bill that increases “disclosure,” the bill itself is not transparent about its convoluted requirements. Specifically, the bill would:

-

-

- Further complicate Connecticut’s existing and exceedingly unclear PAC registration and reporting requirements for organizations that engage in any political speech, issue speech, or nonpartisan voter education.

- Groups that engage in such activities are currently required to file reports only whenever their spending exceeds $1,000 and only report donors of $5,000 or more. Unless Connecticut’s PAC definition is clarified, H.B. 7329 could require such groups to file ongoing periodic PAC reports and identify donors who give so much as a penny, as well as effectively impose other unconstitutional bans on organizations’ political activities.

- Worsen Connecticut’s existing infringement on donor privacy and increase misinformation to the public by requiring groups sponsoring any independent expenditure (“IE”) and PACs to report their donors’ donors.

- Enact a vague and overbroad prohibition on “foreign-influenced entities” based on a defective provision in the federal H.R. 1 bill that congressional sponsors were forced to abandon. The provision would effectively prohibit many domestic subsidiaries and publicly traded American corporations from exercising their constitutional right to fund independent expenditures and contribute to independent expenditure political committees.

- Impose unconstitutionally burdensome recordkeeping requirements on online advertising platforms that would force many affected entities to stop accepting ads in Connecticut.

-

Analysis

A) H.B. 7329 Could Make Connecticut’s Severely Defective Existing PAC Definition Far Worse

H.B. 7329 would update Connecticut’s campaign finance laws by codifying major judicial rulings over the past decade into statute.[3] Specifically, the bill would establish a statutory basis for: (1) “independent expenditure political committees” (commonly known as super PACs)[4]; and (2) corporations making independent expenditures (“IEs”) and contributions to super PACs.[5] IFS supports revising Connecticut statute to acknowledge and comply with these important court decisions.

Unfortunately and inexplicably, H.B. 7329 would not also codify several court decisions regarding when organizations making IEs may be required to register and report as “political committees” (“PACs”), as opposed to simply filing IE reports as non-PAC entities. Relatedly, H.B. 7329 also would not codify the State Elections Enforcement Commission’s (“SEEC”) interpretation addressing Connecticut’s unintelligible existing PAC definition.

The distinction between reporting as a PAC and as a non-PAC entity is critically important. Absent a clarification of this issue in H.B. 7329, groups could be subject to a vast increase in burdensome and invasive PAC reporting requirements and crippling penalties not only for sponsoring electoral campaign ads, but also for discussing issues of public importance and engaging in nonpartisan voter education.

1. Existing Connecticut Regulation of Independent Expenditures and PACs

In order to understand H.B. 7329 and how it could exacerbate Connecticut’s problematic PAC definition, it is first necessary to understand how existing Connecticut law regulates IEs and PACs.

Existing IE Definition. Connecticut defines an “independent expenditure” as an “expenditure . . . that is made without the consent, coordination, or consultation of, a candidate or agent of the candidate, candidate committee, political committee or party committee.”[6]

An “expenditure” is defined broadly to cover spending on any activity or communication “to promote the success or defeat of any candidate seeking the nomination for election, or election, of any person or for the purpose of aiding or promoting the success or defeat of any referendum question or the success or defeat of any political party.”[7]

However, an “expenditure” specifically also includes any public communication that “refers to one or more clearly identified candidates.”[8] Under this mere reference standard, a communication that names any elected official who may run for re-election or candidate is regulated speech. There are only two narrow exemptions for: (a) communications made prior to 90 days before an election in which the candidate is on the ballot and that are “made for the purpose of influencing any legislative or administrative action, as defined in [Conn. Gen. Stat. §] 1-91, or executive action”; and (b) communications made “during a legislative session for the purpose of influencing legislative action.”[9]

Importantly, these exemptions to the mere reference standard do not apply to the general definition of an “expenditure” – i.e., anything that is deemed “to promote the success or defeat of any candidate” or that is “for the purpose of aiding or promoting the success or defeat of any referendum question or the success or defeat of any political party.”

Therefore, the existing law regulates not only speech that would typically be understood as electoral “campaign ads,” but also, for example:

-

-

- Nonpartisan voter guides that provide information about the candidates who are running in an election.[10]

- Nonpartisan reminders to vote if the candidates running in the election are identified.

- Communications within 90 days before an election that urge an elected state official to act, not act, or to take a position on an issue of public importance (communications that urge a “legislative action” also would be covered if the General Assembly is not in session).

- Communications not related to Connecticut “legislative action,” but calling on Connecticut officials to take stands on national issues. For example, an ad urging the governor to “oppose Trump’s policy against sanctuary cities” would be regulated.

-

In addition, under the vague and subjective intent-based general “expenditure” definition, speakers may be regulated if, for example:

-

-

- They promote an issue such as school security, tax reform, health care reform, or gun control, if candidates make these issues part of their campaign platforms; or

- They engage in any activities and are alleged to have the impure “purpose of aiding or promoting the success or defeat of any referendum question or the success or defeat of any political party” – in other words, committing a thought crime.

-

Existing PAC Definition. As discussed more below, H.B. 7329 relies heavily on Connecticut’s existing “political committee” definition. This definition is utterly unintelligible, and H.B. 7329 not only fails to fix it, but could exacerbate it.

Connecticut defines a “political committee,” in relevant part, as “(A) a committee organized by a business entity or organization [or] (B) persons other than individuals, or two or more individuals organized or acting jointly conducting their activities in or outside the state.”[11]

Right out of the gate, this definition is nonsensical. As it is written, the phrase “committee organized by” only modifies the clause in part (A), but does not also modify the clause in part (B). Therefore, any two people walking down the street together in Danbury, England and minding their own business could be regulated as a Connecticut “political committee” for “acting jointly conducting their activities in or outside the state.”[12]

Even assuming the phrase “committee organized by” is meant to modify clause (B), the term “committee” is still unavailing. The statute unhelpfully defines a “committee,” in relevant part, as a “political committee . . . organized . . . to aid or promote the success or defeat of any political party, any one or more candidates for public office . . . or any referendum question.”[13]

Connecticut’s “political committee” and “committee” definitions reference each other and are circular. This type of “circular definition provides no guidance,”[14] and therefore is unconstitutional because it fails to “give the person of ordinary intelligence a reasonable opportunity to know what is prohibited.”[15] This is especially so where, as here, a law regulates “sensitive areas of basic First Amendment freedoms,” and the unintelligible law “operates to inhibit the exercise of those freedoms.”[16]

For example, under a literal application of Connecticut’s “political committee” definition, two people walking down the street putting up yard signs promoting a candidate must register and report as a PAC. This is because they are “two or more individuals… acting jointly” (from the “political committee” definition) to “aid or promote the success or defeat of… candidates” (from the “committee” definition). But surely not every instance of two or more individuals acting together to promote candidates in this manner is a PAC that is required to register with the state and file ongoing periodic reports of their spending and donors.

2. H.B. 7329’s Failure to Fix, and Reliance on, Connecticut’s Defective PAC Definition

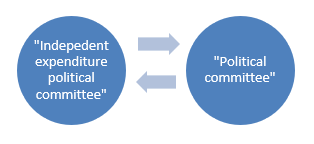

H.B. 7329 would create a new type of PAC known as an “independent expenditure political committee,” which the bill defines as “a political committee that makes only (A) independent expenditures, and (B) contributions to other independent expenditure political committees.”[17]

The bill would also add to Connecticut’s existing “political committee” definition “an independent expenditure political committee.”[18]

In short, H.B. 7329 extends and exacerbates Connecticut’s defective PAC definition by defining an “independent expenditure political committee” as a form of “political committee,” which in turn is defined as an “independent expenditure political committee”:

H.B. 7329’s unintelligible runaround definition is particularly pernicious because an entity that fails to properly report as an “independent expenditure political committee” could be liable for penalties of up to $50,000 or ten times the amount spent on an IE, and the entity’s chairperson and officers also may be held personally liable.[19]

On its face, H.B. 7329 also makes Connecticut’s PAC definition even more puzzling by requiring any “person who makes or obligates to make an independent expenditure or expenditures in excess of [$1,000], in the aggregate,” to “file statements according to the same schedule and in the same manner as is required of a treasurer of a political committee,” and to file additional reports “for each subsequent independent expenditure made or obligated to be made.”[20] This appears to imply that certain organizations (which are “persons”[21]) that make IEs are not required to register and report as PACs, but rather must file reports for their IEs “in the same manner as” a PAC, and only when IEs are made (as opposed to the ongoing periodic reports that PACs are required to file).[22]

However, H.B. 7329 fails to specify when an organization making IEs is required to file reports “in the same manner as” a PAC, and when the organization is required to register and report as a full-fledged PAC. Adding to the confusion, H.B. 7329 would recodify language in the existing statute providing that “[a]n organization may make contributions or expenditures, other than for the purpose of promoting the success or defeat of a referendum question, only by first forming its own political committee.”[23] This language suggests that any and all organizations that make any regulated expenditures (including IEs) must register as PACs and file PAC reports – which renders H.B. 7329’s apparent alternative IE reporting regime for non-PAC entities superfluous (unless the standalone IE reports are meant to apply only to individuals).

The analysis of H.B. 7329 by the General Assembly’s Office of Legislative Research (“OLR”) suggests a way to resolve this interpretive cul-de-sac. The OLR implies the bill would preserve the SEEC’s existing IE reporting regime, under which “incidental spenders” are not required to register and report as PACs merely as a result of making IEs.[24] If this theory is correct, it would explain the bill’s apparently inconsistent provisions addressing standalone IE reports and independent expenditure political committee registration and reporting requirements.

But this game of “hide the ball” is no way to write a bill. Relying on a separate explanatory OLR analysis that would not be codified into the Connecticut statute to bring coherence to otherwise unintelligible bill text is legislative malfeasance. Moreover, if H.B. 7329 is going to bother codifying judicial holdings on IEs and super PACs into the statute, then why not also codify the SEEC’s interpretation? Why force the public to guess at what the statute means and search separately for obscure guidance from the OLR and SEEC that lacks the force of formal law?

Specifically, under the SEEC’s existing regulatory approach, groups that are “incidental spenders” or “incidental reporters” are not required to register and report as PACs when making IEs in Connecticut.[25] The SEEC defines an “incidental reporter” as an organization that makes IEs only using “funds from [its] general treasury which were not solicited or received for use in Connecticut elections.”[26] If, in fact, H.B. 7329 intends to preserve this regulatory approach, then it should say so explicitly by codifying the SEEC’s “incidental reporter” definition into the statute and specifying that the persons that are required to file IE reports “in the same manner as is required of a PAC” are “incidental reporters.”[27]

The following chart illustrates why it is so critical for H.B. 7329 to clarify in the statute when groups making IEs are only required to file as “incidental reporters,” and when they are required to register and report as PACs:

| “Incidental Reporter” Requirements | PAC Requirements | |

| Frequency of Reports | Reports are required only whenever IEs are made that total more than $1,000.[28] | Ongoing periodic reports are required, regardless of whether IEs are made during the reporting period.[29] |

| Identification of Donors | Donors who have given $5,000 or more during the 12-month period preceding the upcoming election are required to be identified.[30] | All contributors who have given during the reporting period must be identified, regardless of the amount they have given.[31] |

| Ability of Corporations and Organizations to Make IEs and Maintain Employee- or Member-Funded PACs | Corporations and organizations that make IEs as “incidental reporters” are not subject to any prohibition on also maintaining an employee- or member-funded PAC. | If corporations and organizations categorically must register and report as “independent expenditure political committees” in order to make IEs, then they effectively may not also maintain an employee- or member-funded PAC. (This is discussed more in Section B on the following page.) |

As the U.S. Supreme Court has noted, “PACs are burdensome alternatives; they are expensive to administer and subject to extensive regulations.”[32] Accordingly, corporations and organizations must be permitted to fund independent expenditures (and, by extension, also contributions to super PACs) directly using general treasury funds, and may not be forced to form PACs in order to engage in such activities.[33] Relatedly, the U.S. Courts of Appeals for the Seventh and Eighth Circuits have both held that it is unconstitutionally burdensome for states to impose ongoing PAC reporting requirements on organizations that only occasionally make IEs, rather than the “event-driven” reporting triggered by making specific IEs that the SEEC currently (and correctly) requires.[34]

In short, by failing to clarify when organizations making IEs are required to simply file IE reports versus when they are required to register and report as PACs, H.B. 7329 does not properly implement important judicial holdings and makes the bill susceptible to a constitutional challenge. This is especially so because, as noted above, the burdensome PAC requirements could be triggered by groups that engage exclusively in issue advocacy or nonpartisan voter education, and not what is typically thought of as electoral campaign advocacy.[35]

Although it may be beyond the scope of what the General Assembly is willing to cover with this bill, we also note that Connecticut’s PAC definition is unconstitutional because it fails to limit its reach only to those organizations whose “major purpose [] is the nomination or election of a candidate” (and/or the passage or defeat of a ballot measure).[36]

B) H.B. 7329 Would Unconstitutionally Force Many Corporations and Organizations to Choose Between Forming an “Independent Expenditure Political Committee” Versus Maintaining an Employee- or Member-Funded PAC

While H.B. 7329 purports to recognize and comply with existing judicial rulings allowing corporations and organizations to make IEs, what one hand giveth, the other taketh away. Specifically, H.B. 7329 would preserve the provisions under existing Connecticut law that prohibit a corporation or nonprofit organization from forming more than one PAC.[37] Effectively, these provisions would force corporations and nonprofit organizations to choose between forming an “independent expenditure political committee” versus maintaining an employee- or member-funded PAC that makes direct contributions to candidates and political party committees. They could not do both.

There is no constitutionally permissible justification for imposing such a binary choice that would satisfy the “strict scrutiny” or “closely drawn” scrutiny standards for judicial review of expenditure and contribution bans, respectively.[38] Indeed, under federal law, it is understood that it is unconstitutional to prohibit an organization from making “both independent expenditures . . . with ‘soft money’ [i.e., funds that are not subject to the contribution limits and corporate source prohibition] and direct contributions to [] candidates and political parties with ‘hard money’ [i.e., funds that are subject to the contribution limits and corporate source prohibition].”[39]

The one-PAC-per-entity restriction under the existing Connecticut law appears to be an anti-proliferation or anti-circumvention rule. It prevents any corporation or organization from forming multiple PACs, each of which could make a separate contribution up to the maximum permitted amount to the same candidates or party committees, thereby circumventing the contribution limits that apply to a single donor. However, as H.B. 7329 recognizes, there are no limits on expenditures by “independent expenditure political committees” or on contributions to such committees. Therefore, there is no legal or policy rationale for prohibiting a corporation or organization from forming both an “independent expenditure political committee” and an employee- or member-funded PAC, as H.B. 7329 would do.

This one-PAC-per-entity restriction would be especially pernicious if, as discussed above, H.B. 7329 does not intend to preserve Connecticut’s existing provision for non-PAC entities that make IEs to file as “incidental reporters,” and instead requires any entity that makes even one IE to first register as an “independent expenditure political committee.” In that case, H.B. 7329 would effectively and unconstitutionally prohibit a corporation or organization that has an employee- or member-funded PAC from making any IEs whatsoever, or vice versa.

C) H.B. 7329 Would Effectively Ban Many Corporations From Making or Supporting IEs Altogether

H.B. 7329 also would effectively and unconstitutionally ban many American corporations from making IEs and contributions to super PACs under an excessively vague and broad definition of “foreign-influenced entity.”[40] Specifically, the bill defines a “foreign-influenced entity” as:

any entity of which (A) one foreign owner holds, owns, controls or otherwise has directly or indirectly acquired beneficial ownership of equity or voting shares in an amount equal to or greater than five per cent of total equity or outstanding shares of voting stock, (B) multiple foreign owners hold, own, control or otherwise have directly or indirectly acquired beneficial ownership of equity or voting shares in an amount equal to or greater than twenty per cent of total equity or outstanding shares of voting stock, or (C) any foreign owner participates in any way, directly or indirectly, in the process of making decisions with regard to the making of expenditures or contributions by such entity.[41]

This definition appears to be based largely on the foreign national definition in the federal H.R. 1 legislation as it was originally introduced in the U.S. House of Representatives.[42] However, this expansive and vague definition proved to be such a problematic and indefensible overreach that H.R. 1’s sponsors were forced to drop the language in the version of the bill that ultimately passed the House.[43] The original language in H.R. 1 was replaced by a definition that follows Federal Election Commission guidance.

As IFS noted of the original version of H.R. 1, this expansive and vague definition of a “foreign national” (or “foreign-influenced entity,” in the case of H.B. 7329) would prohibit all domestic subsidiaries that have a foreign parent from participating in the political process.[44] These companies – which employ more than 100,000 Connecticut residents[45] – should not be banned from speaking about political issues that affect their Connecticut employees’ livelihoods.

Like the original version of H.R. 1, H.B. 7329 also would pose insurmountable challenges to publicly traded companies – 17 of the largest of which are headquartered in Connecticut.[46] Many of these companies each have millions of their shares change hands daily[47] and shareholders who own shares through intermediary entities (such as mutual funds). It would be practically impossible for any publicly traded company to determine with certainty at any given time whether they trigger the five or 20 percent thresholds in H.B. 7329 for becoming a “foreign-influenced entity” by virtue of foreign nationals “directly or indirectly” owning shares.

In short, H.B. 7329’s “foreign-influenced entities” provision effectively bans many corporations from exercising what the U.S. Supreme Court has affirmed are their core First Amendment rights.

D) H.B. 7329 Would Worsen Connecticut’s Existing Invasion of Donor Privacy and Misinformation to the Public

Existing Connecticut law already requires excessive reporting of donors on IE reports. As discussed in the chart on page 7, groups that make IEs must report donors regardless of whether they give specifically to support the funding of the IE being reported. Far from achieving any meaningful disclosure or providing useful information to the public, this indiscriminate reporting requirement leads to “misinformation to the public about who supported the advertisements” by associating donors with ads they do not necessarily support.[48]

H.B. 7329 would make Connecticut’s existing donor identification requirement even worse by requiring sponsors of IEs and PACs to report not only their donors, but their donors’ donors. If a reported donor has given more than $1,000 to the organization or PAC (whom we shall call “Donor Prime” for the sake of clarity), Donor Prime’s own donors who have given more than $5,000 in total to Donor Prime during the 12 months prior to the upcoming election also must be identified on the report.[49]

This requirement further exacerbates the problem alluded to above of “junk disclosure.” Under H.B. 7329, the link between the donors reported and the IE being reported would become even more attenuated and meaningless to a point approaching “six degrees of separation.” It is doubtful that such a far-reaching, indiscriminate, and overbroad donor reporting requirement could satisfy the “exacting scrutiny” constitutional standard for campaign finance reporting laws, which demands a “substantial relation between the disclosure requirement and a sufficiently important governmental interest.”[50]

As a practical matter, H.B. 7329 also would impose an effective prior restraint or prohibition against many donations to nonprofit groups. The bill makes recipient organizations and their donors jointly responsible for providing and collecting the donors’ donors’ information prior to making and accepting a donation of more than $1,000.[51] It is doubtful that most donors would have such information readily available or be willing to provide it, and this will infringe on the freedom of association between donors and organizations by making donations more difficult.

Notably, the New York City Board of Elections recently pulled a list of voters’ names, addresses, and party affiliation that it had posted online after coming under withering criticism.[52] “Privacy experts worried that the ready availability of the information could endanger domestic violence survivors and others who might be subject to harassment, stalking or mail spam.”[53] Governor Andrew Cuomo noted his concern of “[p]utting people’s personal information online – in this new world, we’re worried about hacking, we’re worrying about identify theft… People can take it and use it to bad effect one way or the other.”[54]

The donor reporting requirements that H.B. 7329 would expand include exactly the same type of information – donors’ names, addresses, and which political causes they support[55] – that Connecticut’s neighbors demanded be kept private.

E) H.B. 7329 Would Impose Unconstitutionally Burdensome Recordkeeping Requirements for Online Advertising Platforms

Lastly, H.B. 7329 would impose complex and onerous recordkeeping requirements on online advertising platforms – including small “mom and pop” blogs that have annual online advertising revenues of as little as $1000.01, or 400,000 or more unique monthly visitors for seven of the past 12 months.[56] The recordkeeping requirements would be triggered by any request to purchase a regulated “expenditure”[57] – which, as discussed above, is broadly and vaguely defined, and covers issue speech and nonpartisan voter education in addition to electoral campaign advocacy.

Advertising platforms that inadvertently violate the recordkeeping requirements by guessing wrong at whether an ad qualifies as an “expenditure” would be subject to penalties ranging from $10,000 to as much as $50,000, or ten times the value of regulated ads for which records are not properly kept.[58]

As the Connecticut Broadcasters Association and Connecticut Daily Newspapers Association have correctly pointed out, H.B. 7329 would cover not only actual ad buys, but mere “requests for advertising,” thereby further exacerbating the bill’s regulatory burden.[59] (IFS incorporates by reference the Associations’ letter opposing H.B. 7329.)

Maryland, which enacted a law last year that is similar to H.B. 7329, should serve as a cautionary example.[60] A federal judge recently determined the Maryland law likely imposes unconstitutional burdens on the websites of various newspapers and enjoined the law from being enforced against them.[61]

Like the Maryland law, H.B. 7329 purports to address “foreign political spending and [] political advertising on social media.” But like H.B. 7329, the judge found the Maryland law to “regulate[] substantially more speech than it needs to while, at the same time, neglecting to regulate the primary tools that foreign operatives exploited to pernicious effect in the 2016 election.”[62] Specifically, it is doubtful that Connecticut could demonstrate that foreign actors are seeking to influence voters through paid advertising on small websites with as little as $1000.01 in annual advertising, or on the many local news websites that H.B. 7329 would cover.[63]

Moreover, as with the Maryland law, H.B. 7329 suffers from the “fundamental defect that it solely targets” paid online advertising, while “the primary evil” involving foreign interference in U.S. elections “was unpaid Internet postings . . . on social media sites . . . Thus, the reach of [H.B. 7329] is dramatically broader than the threat it [is] chiefly [designed] to counter.”[64]

Putting aside the constitutional defects in H.B. 7329, the recordkeeping burdens and liability risk it would impose ensure many online advertising platforms will simply stop selling political and issue ads in Connecticut. The Maryland law, as well as a similar law in Washington State, have already caused Google and Facebook, respectively, to stop selling political ads in those states.[65] If such Internet behemoths are unable to satisfy the regulatory burdens H.B. 7329 would impose, many smaller websites will certainly follow their lead and stop accepting content from Connecticut advertisers.

The outcome will be less speech about issues of public importance in Connecticut, particularly for promoters of minority views and social change movements who rely disproportionately on social media.[66]

Conclusion

Foreign meddling in U.S. elections is unacceptable, but Connecticut state legislators must resist the siren song of countering foreign interference by indiscriminately passing laws that will predominantly harm the rights of Americans to speak and publish. H.B. 7329 would impose unclear reporting burdens on Connecticut residents speaking about issues of public importance in the state. The bill would also worsen Connecticut’s existing overbroad encroachments on donor privacy. Online platforms that accept advertising about public issues would be subject to onerous recordkeeping requirements and enormous liability risk, thereby causing many platforms to stop accepting such content. The inevitable aggregate effect of these provisions is to deter, punish, and reduce speech and information about Connecticut state government, thereby reducing democratic accountability for Connecticut state officials.

[1] Eric Wang is also Special Counsel in the Election Law practice group at the Washington, D.C. law firm of Wiley Rein, LLP. Any opinions expressed herein are those of the Institute for Free Speech and Mr. Wang, and not necessarily those of his firm or its clients.

[2] The Institute for Free Speech is a nonpartisan, nonprofit § 501(c)(3) organization that promotes and protects the First Amendment political rights of speech, press, assembly, and petition. Originally known as the Center for Competitive Politics, it was founded in 2005 by Bradley A. Smith, a former Chairman of the Federal Election Commission. In addition to scholarly and educational work, the Institute is actively involved in targeted litigation against unconstitutional laws at both the state and federal levels. Its attorneys have secured judgments in federal court striking down laws in Colorado, South Dakota, and Utah on First Amendment grounds. The Institute is currently involved in litigation against California, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Missouri, South Dakota, and Tennessee.

[3] See, e.g., Citizens United v. FEC, 558 U.S. 310 (2010); Speechnow.org v. FEC, 599 F.3d 686 (D.C. Cir. 2010); Hispanic Leadership Fund, Inc. v. Walsh, 42 F. Supp. 3d 365 (N.D. N.Y. 2014).

[4] H.B. 7329 § 1 (to be codified at Conn. Gen. Stat. § 9-601(32)).

[5] Id. § 11 (to be codified at Conn. Gen. Stat. § 9-613(g)(1)).

[6] Conn. Gen. Stat. § 9-601c(a).

[7] Id. § 9-601b(a).

[8] Id. § 9-601b(a)(2). The forms of regulated communications are those made by “radio, television . . . satellite communication or via the Internet, or as a paid-for telephone communication, or appears in a newspaper, magazine or on a billboard, or is sent by mail.”

[9] Id. § 9-601b(b)(7).

[10] Connecticut law exempts certain internal communications made within a corporation, organization, or association, but does not exempt communications made with the general public. See id. § 9-601b(b)(2), (3).

[11] Conn. Gen. Stat. § 9-601(3).

[12] If the phrase “organized by” is also meant to modify the clause in part (B), the definition should be rewritten as: “a committee organized by: (A) a business entity or organization [or] (B) persons other than individuals, or two or more individuals organized or acting jointly conducting their activities in or outside the state.”

[13] Id. § 9-601(1).

[14] See, e.g., Comm’n on Human Rights and Opportunities v. Echo Hose Ambulance, 322 Conn. 154, 159 (Conn. 2016) (a “circular definition provides no guidance”), aff’g 156 Conn. App. 239, 248 (Conn. App. 2015) (a “definition that is completely circular [] explains nothing”) (quoting Clackamas Gastroenterology Assoc. v. Wells, 538 U.S. 440, 444 (2003)).

[15] Grayned v. City of Rockford, 408 U.S. 104, 108 (1972).

[16] Id. (internal quotation marks, citations, and parentheses omitted).

[17] H.B. 7329 § 1 (to be codified at Conn. Gen. Stat. § 9-601(32)). Presumably, the bill’s intent is to use the conjunctive “and/or” rather than simply the conjunction “and.” Otherwise, an entity that only makes IEs, or that only makes contributions to other independent expenditure political committees, is not itself an independent expenditure political committee because it does not do both.

[18] Id. § 2 (to be codified at Conn. Gen. Stat. § 9-601(3)).

[19] H.B. 7329 § 3 (to be codified at Conn. Gen. Stat. § 9-601d(i)(2), (3)) (referencing reports filed under Conn. Gen. Stat. § 9-608 (PAC reporting requirements)).

[20] Id. (to be codified at Conn. Gen. Stat. § 9-601d(a)) (emphasis added).

[21] Conn. Gen. Stat. § 9-601(10).

[22] See Conn. Gen. Stat. § 9-608(a)(1).

[23] H.B. 7329 §12 (to be codified at Conn. Gen. Stat. § 9-614(a)) (emphasis added).

[24] Conn. Gen. Assembly, Ofc. of Legis. Research Bill Analysis, H.B. 7329, File No. 755 at 51-52.

[25] SEEC, 24 Hour Reporting of Independent Expenditures for Statewide and General Assembly Candidates, at https://www.ct.gov/seec/cwp/view.asp?a=3563&Q=550054. (The OLR analysis refers to such groups as “incidental spenders,” while the SEEC refers to such groups as “incidental reporters.”)

[26] Id.

[27] See supra note 20.

[28] See supra note 25.

[29] Conn. Gen. Stat. § 9-608(a)(1).

[30] See supra note 25; see also SEEC Form 26 – Long Form (rev. Aug. 2014), at https://www.ct.gov/seec/lib/seec/forms/independent_expenditures/seec_form_26_independent_expenditures_long_form_form_final_082014.pdf; Instructions for SEEC Form 26 – Long Form (rev. Aug. 2014), at https://www.ct.gov/seec/lib/seec/forms/independent_expenditures/seec_form_26_independent_expenditures_long_form_instructions_final_082014.pdf; Conn. Gen. Stat. § 9-601(29) (defining “covered transfer”).

[31] H.B. 7329 § 7 (to be codified at Conn. Gen. Stat. § 9-608(c)(1)(A)).

[32] Citizens United, 558 U.S. at 337.

[33] Id. at 337-39.

[34] Wis. Right to Life v. Barland, 751 F.3d 804, 841-42 (7th Cir. 2014); Iowa Right to Life Comm. v. Tooker, 717 F.3d 576, 597-99 (7th Cir. 2013); Minn. Citizens Concerned for Life v. Swanson, 692 F.3d 864, 875 n.9 & 876 (8th Cir. 2012).

[35] See Wis. Right to Life, 751 F.3d at 838 (invalidating a Wisconsin regulation under which “ordinary citizens, grass-roots issue-advocacy groups, and § 501(c)(4) social-welfare organizations are exposed to civil and criminal penalties for failing to register and report as a PAC if they spend more than $300 to communicate their views about any political issue close to an election and include the name or likeness of a candidate”).

[36] Buckley v. Valeo, 424 U.S. 1, 79 (1976).

[37] H.B. 7329 §§ 11 (to be codified at Conn. Gen. Stat. § 9-613(a)) (“A business entity shall not establish more than one political committee”), 12 (to be codified at Conn. Gen. Stat. § 9-614(a)) (“An organization shall not form more than one political committee”).

[38] See, e.g., Citizens United, 558 U.S. at 340; McCutcheon v. FEC, 572 U.S. 185, 197 (2014); see also Green Party of Conn. v. Garfield, 616 F.3d 189, 199 (2nd Cir. 2010).

[39] Carey v. FEC, 791 F.Supp.2d 121, 130 (D. D.C. 2011); see also, e.g., FEC, Registering as a Hybrid PAC, at https://www.fec.gov/help-candidates-and-committees/filing-pac-reports/registering-hybrid-pac/.

[40] H.B. 7329 § 19 (Conn. Gen. Stat. codification unspecified).

[41] Id. § 1 (to be codified at Conn. Gen. Stat. § 9-601(35)) (emphasis added).

[42] Compare id. with H.R. 1 (116th Cong.), as introduced on Jan. 3, 2019, § 4101.

[43] Compare H.R. 1 (116th Cong.), as introduced on Jan. 3, 2019, § 4101 with H.R. 1 (116th Cong.), engrossed in House on Mar. 8, 2019, § 4101.

[44] IFS, Analysis of H.R. 1 (Part 1) (Jan. 2019) at 10, available at https://ifs-site.mysitebuild.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/2019-01-23_IFS-Analysis_US_HR-1_DISCLOSE-Honest-Ads-And-Stand-By-Every-Ad.pdf.

[45] Organization for International Investment (OFII), Connecticut, at https://ofii.org/state/connecticut.

[46] Russell Blair, These 17 Fortune 500 Companies Are Headquartered In Connecticut, Hartford Courant (May 23, 2018), at https://www.courant.com/business/hc-biz-connecticut-fortune-500-companies-20180522-story.html.

[47] See, e.g., Yahoo Finance, Most Actives, at https://finance.yahoo.com/most-active (see “Volume” column).

[48] Van Hollen v. FEC, 811 F.3d 486, 497 (D.C. Cir. 2016).

[49] H.B. 7329 § 7 (to be codified at Conn. Gen. Stat. § 9-608(c)(4)).

[50] Citizens United, 558 U.S. at 365 (internal quotation marks and citation omitted).

[51] H.B. 7329 § 7 (to be codified at Conn. Gen. Stat. § 9-608(c)(6), (7)).

[52] Vivian Wang, After Backlash, Personal Voter Information Is Removed by New York City, N.Y. Times (Apr. 30, 2019), at https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/30/nyregion/nyc-personal-voter-information-election-board.html.

[53] Id.

[54] Id.

[55] H.B. 7329 § 7 (to be codified at Conn. Gen. Stat. § 9-608(c)(1)).

[56] H.B. 7329 § 23(a)(1) (Conn. Gen. Stat. codification unspecified).

[57] Id. § 23(a)(2), (c).

[58] Id. § 23(g).

[59] Conn. Broadcasters Assoc. and Conn. Daily Newspapers Assoc., Letter to Conn. Gen. Assembly Gov’t Admin. & Elections Comm. (Apr. 22, 2019), available at https://www.ctnewsjunkie.com/upload/2019/04/CBA_CDNA_Dark_Money_Letter.pdf.

[60] See Md. Code, Election Law § 13-405; see also IFS, Analysis of “Online Electioneering Transparency and Accountability Act” (Apr. 5, 2018), at https://ifs-site.mysitebuild.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/2018-04-05_IFS-Analysis_MD_HB-981_Online-Ad-Disclaimers-And-Reporting.pdf.

[61] The Wash. Post v. McManus, No. 1:18-cv-02527, memo op. (D. Md. Jan. 3, 2019).

[62] Id. at 38.

[63] See id. at 41.

[64] Id. at 41-42 (emphasis in the original).

[65] See Google, Political Content, at https://support.google.com/adspolicy/answer/6014595?hl=en; Michael Dresser, Google no longer accepting state, local election ads in Maryland as result of new law, Baltimore Sun (Jun. 29, 2018), at https://www.baltimoresun.com/news/maryland/politics/bs-md-google-political-ads-20180629-story.html; Facebook, New Rules for Ads That Relate to Politics in Washington State (Dec. 27, 2018), at https://www.facebook.com/business/news/new-rules-for-ads-that-relate-to-politics-in-washington-state.

[66] See, e.g., Jessica Guynn, Facebook while black: Users call it getting ‘Zucked,’ say talking about racism is censored as hate speech, USA Today (Apr. 24, 2019), at https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/2019/04/24/facebook-while-black-zucked-users-say-they-get-blocked-racism-discussion/2859593002/ (“The rise of #BlackLivesMatter and other hashtag movements show how vital social media platforms have become for civil rights activists. About half of black users turn to social media to express their political views or to get involved in issues that are important to them, according to the Pew Research Center. These hashtag movements, coming against the backdrop of an upsurge in hate crimes, have helped put the deaths of unarmed African Americans by police officers on the public agenda, along with racial disparities in employment, health and other key areas.”).